Message from the Editor

Membership Letters

ICS NEEDS YOUR HELP! 30 DAYS LEFT IN DRAWING!

Dear ICS Members,

Happy New Year! So much has happened in the real world that less time has been spent in the cyber-world. Last year the Internet Cello Society upgraded to the current interactive website that allows all members to add entries to the many different sections of our website. Unfortunately, the idea of being assistant webmasters has not taken off on its own. So I would like to challenge all of you to get in there and add entries to your favorite section of the ICS website! Do you like to collect clip art? Any rare photos of cellists or cellos that you have been meaning to share with the cyber-world? We really need someone to take some time to add some historical cellists to our database too!

We need your help!

Please help build the ICS website by adding and modifying entries in the different databases! For instructions see the ICS FAQ at http://cello.org/faq.htm.

and/or

We need your help now to continue debugging the new ICS website and to pursue some major upgrades. Our tax return in 2001 included $4,137 in expenses and only $1,681 in income. This year�s monthly bills total over $300 a month for hosting services, Coldfusion Internet database programming, credit card merchant lease payments and fees, internet connection and software costs. The ICS Staff continues to be entirely volunteer, though eventually it would be nice to compensate those staff members like Tim Janof who contribute enormous amounts of time and energy to ICS.

As many of you have noticed, the new website, though now an interactive site, has bugs and is slow to upgrade. There are two main reasons for this: 1) the site is in Coldfusion database language, which means I am no longer able to program the website myself and 2) our Coldfusion programmer is professional and therefore his time is limited and compensated. Currently Eric Hoffman is our Coldfusion programmer as well as our webmaster (he volunteers his time as webmaster). Professional Coldfusion programming costs between $55-75 per hour, though Eric has been generously offering his services for less.

Our goal is to raise $4500 to pay for some major upgrades next year. Please make your contribution soon! From those who contribute three names will be randomly selected at the end of January 2003 to receive a free ICS souvenir of their choice, including "ASK BETTY LOU!"/ICS t-shirts, mugs, clock, frisbee, hats or mousepad! To see prizes or to buy your own souvenir see http://www.cafepress.com/cello.

Best wishes to you and your cello this coming year,

John Michel

ICS Director

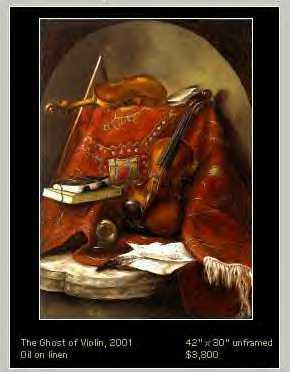

>> I saw the list of cello pictures in the last newsletter. Here are a couple of pictures that were painted by my cello student, Jenny Chi, who is also the new art professor at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois.

Barbara Hedlund

>> Zara Nelsova was my teacher from the end of the 70's until our last series of lessons in Aspen in 1981. She taught me details of technique that I still use and pass on to my own pupils. I find it a great loss for our cello world, and for myself, as she always gave me the impression of being friends from the beginning of my studies with her. Because I live in Amsterdam and have worked since 1968 as a cellist in the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, she taught me during her stay (when playing solo) in Amsterdam or elsewhere in Europe. I would travel to her after having prepared a full program. During the summer of 1981 (I was married to Bernard Haitink at the time), we worked for five weeks at her place, and then in Aspen, where we became friends. For many years, when our orchestra went to New York, I visited her apartment. We drank vodka, had a lovely homecooked (grandmother-style) meal, and laughed like sisters. She often thought of writing her memoirs -- I hope she did!!

Especially during the last few years, I couldn't get in touch with her and I didn't know that she was so ill. She probably didn't want us to know. I look forward to writings about her life.

Saskia van Bergen-Boon

>> I'd like to express my admiration for your internet work. Your website provides me with a lot of pleasure and advice. I'm a cello teacher at the Conservatory in Brno (Czech Republic), which was founded by Leos Janacek. I have translated a lot of your articles into Czech and have given them to my students to read and to think about. For many years, there has been little information available in our country. I am trying to fill this void in knowledge of the American cello school, methodology, and history.

Vaclav Horak

>> I'm a piano teacher and performer in Malaysia. I would like to take cello lessons as my second instrument, but I'm having doubts, due to my age and zero knowledge on cello playing. I'm 25 and I would like to ask if it's too late to start at my age? Is there any disadvantage if I start now? I really hope you can help me as I really want someone who is a professional cellist to ease my doubts.

Robert Jesselson replies: I really don't think it is ever too late to start to play an instrument and to enjoy it. That doesn't mean you will become a professional on it, but you can do it for your own enjoyment, with the possibility of playing chamber music or in an amateur orchestra. There is even a book by Noah Adams, called Piano Lessons: Music, Love and True Adventures, published by Delacorte Press, which is the story of a "late bloomer" on the piano.

Actually, I started playing the cello seriously at age 21 -- though I then spent five years of 10-hour days in Germany practicing -- but I had a goal of becoming a professional musician. It was hard work, but I am glad that I did it (that was 31 years ago when I started!).

Best wishes, and good luck with your adventures on the cello!

>> My ICS contribution this year was a Christmas present to myself. I've made such intensive use of the site during the last year (especially the Forums). Thank you for all your hard work.

Susan

>> In response to a letter in the last newsletter, I have played for many years and have travelled all over with my cello. Never have I ever loosened the strings or put the sound post down. A good quality hard case (Kolstein is the best) and some tender loving care during travel is all I have ever needed. When you take the sound post down you get into all kinds of long drawn out trouble in getting it back in place after you arrive at your destination, and again when you return home. I would never recommend resetting the sound post on your own, and some luthiers can be costly. Your best bet is to invest in a good hard case, and then just enjoy your travels.

Jamie Crouch

**If you would like to respond to something you have read in 'Tutti Celli',

write to editor@cello.org and type "Membership

Letter" in subject field. (Letters may be edited.)**

by Tim Janof

As cellist with the Borodin Piano Trio and former Professor at the University of Houston (retired July 2000), he was a member of the Léner and Canadian String Quartets, Trio Concertante, and Crown Chamber Players. Mr. Varga received the distinguished title of "Chevalier du Violoncelle" from Indiana University for prestigious cellists who have dedicated their careers and teaching to the improvement of the art of cello playing. He has taught at the University of Toronto, Stanford, San Francisco State, University of California at Santa Cruz, and the University of Houston. Many of his former students hold positions in symphony orchestras and universities throughout the world.

As a conductor, he led the Budapest Symphony, San Leandro Symphony, and the Aspen and Shreveport Festivals. He was the founder and conductor of the "Virtuosi of New York" and "Virtuosi of San Francisco." He formed the first cello quartet in America in the 1950's and spawned a worldwide movement of cello ensembles. He frequently gives master classes and recitals and guest conducts mass cello ensembles at cello congresses around the world. His arrangements are available from MusiCelli Publications -- the world's largest collection of his editions. His editions have been recorded by the Yale Cellos, Saito Cello Ensemble, CELLO for Sony/Phillips, MusiCelli, the Los Angeles I Cellisti, and by his New York Philharmonic Cello Quartet on DECCA Records.

TJ: You grew up in Hungary. Did you know Janos Starker?

LV: Yes, we studied with the same cello teacher, Adolf Schiffer, at the Music Academy in Budapest. Starker was a true child prodigy, while I was a bit of a late bloomer. He was already performing the Kodály Solo Sonata when he was eleven years old! Starker left the Academy after Schiffer retired, while I stayed and continued my studies with Miklós Zsámboki and Eugene Kerpely, the latter to whom Kodály dedicated his Solo Sonata.

Starker started concertizing as a soloist very early, so our paths diverged for a few years, but then I started to catch up with him. In fact, our paths were fairly parallel for many years. For example, at the end of World War II, I was the principal cellist in the Budapest Symphony at the same time he was the principal cellist in the Budapest Opera. Then I was the principal cellist of the New York Philharmonic while he was the principal cellist of the Metropolitan Opera.

(Click here for the complete transcript.)

Having never seen a Baroque dance, how could I know if this statement is correct? I've read a couple of books on Baroque dance, but, like learning to play the cello, a one can't get an intuitive sense of such a kinesthetic subject from a book.

As luck would have it, I recently discovered that Anna Mansbridge, a Baroque dance specialist, had moved to my hometown, Seattle. She hails from the United Kingdom, where she studied for many years with teachers foremost in the dance profession. She holds degrees from Bedford College (UK) and Mills College in California. She has taught and performed Baroque dance in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe, including Norway, Sweden, and Croatia. A resident of Seattle since 1998, she returns to Europe regularly to stage operas and teach early music courses. In 1995 she co-founded Footwork OffLimits, a dance company that blends early and modern dance genres. In Seattle, where she teaches Baroque dance, she is the artistic director of Seattle Early Dance and an artist-in-residence for the Washington State Arts Commission (2001-2003). I could finally pose my many questions to a Baroque dance specialist and watch her dance allemandes, courantes, bourrées, etc.

(Click here for the complete transcript.)

by Annette Morreau

It's been an amazing adventure. Effectively, it all started in my childhood. I was a cellist, the daughter of a professional viola player -- Beryl Scawen Blunt who at 16 was an advanced player at the Royal College of Music in London and who went on to be the first viola member of the Macnaghten String Quartet, a quartet modelled on the Kolisch Quartet. After studying cello at Dartington Hall, I went on to read music at Durham University, where I became the first woman to win the Durham/Indiana University Scholarship. In 1966, I ended up in Bloomington where, after a couple of alarming lessons from Janos Starker, I decided that a career as a solo cellist was highly unlikely. But I did start a thesis on the string quintets of Boccherini....

My career remained in music. From the Arts Council of Great Britain, where I founded the Contemporary Music Network, a national touring scheme for new music that was heavily influenced by my Bloomington experience -- why play a piece, especially a new piece, only once after so much practice? -- I went on to be Commissioning Editor for Serious Music at Channel 4 Television, and then an independent radio and TV producer and music critic for various publications, including the Independent newspaper.

In 1991, I was invited by the newly founded BBC Music Magazine to review Pearl's 6 CD set: 'The History of the Cello on Record.' I was entranced and as a result met Keith Harvey, the youngest Principal cellist in his time of any London orchestra and a collector extraordinaire, who had supplied Pearl with the precious 78s. We made seven programmes for the BBC World Service about the cellists and Feuermann was one of them. I had never heard such playing as Feuermann's and I suggested to Keith that we try to interest BBC Radio 3 in some programmes. In 1994 my 'Feuermann Remembered,' four two-hour programmes, was broadcast (and again in 1996). In the course of the research for these programmes, I discovered that the Reifenbergs who welcomed the young prodigy into their lives in Cologne where Feuermann at the age of 16 had been appointed Professor at the Conservatory, were distant relatives of my family. When I met Feuermann's widow, Eva [née Reifenberg], she gave me many letters including one from Feuermann to her on my grandmother's headed note paper with a postscript in my grandmother's handwriting.... Had my mother still been alive she would have reminded me of the story of Feuermann visiting my grandmother and leaving the Strad in the passageway with children and dogs jumping around. My mother 'rescued' the instrument, putting it up on the piano. So my professional interest in Feuermann turned into a family one too.

(Click here for the complete transcript.)

(Click here for the complete transcript.)

I seek your help because I think I may be in real trouble here. I have played cello for nearly 15 years and it all may be for nothing. I started out with a cruel teacher who played psychological tricks on me, like skipping me a few levels ahead to see how I reacted to such pressure. I then switched to a teacher who showed me playing the cello is more than making pitches and rhythms sound on the instrument, that you should say something with music. Then I went applied to university and did not have the funds to go where I wanted to go, to study with my cello-hero. So I went to a school close to home, which gave me a free ride and had an ok teacher but overall was not a good school. Then I decided to audition (and I got in) to a much better school, a well-known conservatory that was on a totally other level. I went to that school, and am still there, and will graduate next year. I do find here that no one makes music, here you're good if you can play fast and loud and in-tune, and that's it. It sickens me. I have decided to just make music myself and not let these idiots influence me.

Now to my real problem: I hate to practice. I HATE it. I love to play, but I would rather do anything but practice. I never really, I mean really, practiced before last year. I played but I never really took anything apart. I've now reached the highest level I can get to without practice. I can do one good week of steady practice, and then I lose it and just sit at home or do something else. I was just diagnosed with ADD, and I thought that would solve everything, that part of the reason I hated practice was that I couldn't concentrate. I guess that was part of the reason, but now I know I just hate it. What do I do? I don't love anything else like I do the cello, but I just cannot get myself to practice regularly. What do I do? Should I quit? Should I just be mediocre and live with it? Will I be able to get a job? What to do?

Oh, and my cello teacher died recently and now I have no idea what kind of person the school will get to replace him ... it looks like they don't care what we want, so I might not even have a semi good teacher. With the loss of my teacher I feel even more alone than before. What should I do?

thanks,

Christine

Dear, sweet, tender Christine,

Honey, you've been through the ringer, and it sounds like you may be going through it a few more times in the near future. You've had some tough breaks, doll, and I applaud you for even getting out of bed every day! My advice is to not make any definite goals or resolutions; you'll just be disappointed and depressed should they not be realized. BettyLou NEVER makes New Year's Resolutions, or sets any goals during the year. That way, everything you do is a success! Take one day at a time, practice only when you want, see if the ADD medication works, and assess you're situation in a few months. Your practice muse is not a lengthy visitor, I wonder why? How on earth do you expect to get anywhere without practice? Of course there will always be opportunities in the proud community orchestras that pepper our landscape should your practice-free studies fall short elsewhere. In the meantime, supplement your "practice time" with listening to some of the old Masters.

By the way, "Making music," honey, is the only way to go, playing fast and loud will only burn you out. You're sensitive; I can see that, so make your own path through your campus, which seems to be studded with smug, boring technicians. I know that type all too well! In the long run, I guarantee, you'll be better off. Please let me know how everything works out doll.

(Click here for the complete transcript.)

This is a website dedicated to the memory of the great Russian cellist, Daniil Shafran.

**Please notify Tim Janof at editor@cello.org

of interesting websites that you would like to nominate for this recognition

in the future. Websites will be selected based on their content, cello relevance,

creativity and presentation style!

ICS Forum Hosts have been asked to check your posts regularly. In this way,

not only the forum hosts, but the entire membership and Internet community

see your message! You are still welcome to contact the forum hosts directly.

For a complete list of ICS Forum Hosts please see http://www.cello.org/The_Society/Staff.html**

>> Bolognini

Ennio Bolognini, Toscanini's godson, was a truly great cellist. This, despite the fact that, unfortunately, his name has now faded from the memories and lips of so many admirers that are no longer able to tell their tales. Here is a story that came directly from him.

He told me that he made that famous recording of "Serenata" in a church in Los Angeles, where he had also recorded a work of Bach, I believe the Adagio in a minor with organ accompaniment. The church had a beautiful built-in organ perfect for the occasion. He was not especially pleased with the quality of the re-play sound on the "Serenata." It was too dry and brittle for that music. "No resonance," he said.

At one point in the session he went to the bathroom. After a moment's reaction to the acoustics in the men's room after the "cascading of great water," which was all marble, and echo-y as any room on the planet, he implored the engineers to get as much cable as possible and bring the microphones into the bathroom. This was done in short order.

He brought in the cello and started playing. It was the perfect sound he wanted especially for the question and answer element of a loud sound followed by a faint echo. Not to mention the reverberance of the pizzicato scale at the end. "A winner!" he said. And that is how it remained on the record!

I will not venture to tell you where he sat when making the recording, as it might shock you and some readers out there. But needless to say, a seat was waiting for him so it was not necessary to bring in a chair for that part of the record, nor was an accompanist needed. Despite the somewhat 'cramped quarters,' the slight lack of bow room was immediately taken into consideration; he had one of the most amazing bow arms of any cellist I have seen before or since. But why not? For that sound he would play standing on his head if necessary.

That was Bolognini, unabashed, humble and proud at the same time, and one of the warmest people I have ever met.

I took Super-8 movies at the time of him playing his famous cello in the front yard of his home in Las Vegas. He was shirtless and the temperature was over 100 degrees. Even though they are silent, you can see how he effortlessly navigated the fingerboard with the largest hands I have ever seen on any cellist.

He was a professional boxer and sparring partner for the World Champion in his youth. Actually, that is how he first came to the US.

Shortly after that filming session, he did me the great honor of asking me to sign his cello. It was his way of collecting a permanent souvenir of his admirers. The table of the cello was literally filled with names from the top to bottom that would make your eyes pop out. Every famous musician he ever knew had contributed to that autograph collection. At the age of 22, I was truly humbled to find myself in such company, an honor I rank it as one of the highest I've ever received, ever.

You might wish to know that his widow at his request left the cello to the Smithsonian Institute where it happily, though quietly, rests to this very day.

Recently, I was asked by its curator if I might present an evening at the Smithsonian. In addition to playing on their "Servais" Strad and the other great ones they own, they asked if I would also play on Bolognini's cello. Of course I said YES and cannot wait for that moment. It will be a thrill and bring back untold memories of one of our greatest cellists. The cello also deserves to be heard for Ennio's sake.

I think it is imperative that we keep alive the memory of these great "ancestors" by playing their works and telling our students about them, (in this case playing what they have left in recordings, when possible) to keep the flame alive. They represented what is today a lost generation that brought a quality of performance and character that we must cherish and pass on to the future generations in our teaching and playing, if possible.

Stephen Kates

>> More on "Two Schools of Thought" (see the last newsletter)

I won't even try to attribute the different performers to the two groups, since my skills as music listener are still very rudimentary, but the whole idea of the two groups reminded me very strongly of a controversy, or rather dichotomy, that ran through a lot of the artistic history of the Western civilization (about the other cultures, I wouldn't know), the opposition, that is, between art as "divine madness," inspiration, enthusiasm in the ancient Greek meaning, and art as a craft, whose perfect mastery and control open the doors to the sublime. Romanticism vs. classicism, to term it very roughly and to use terms that have been coined comparatively recently.

It would seem to me that the followers of the first approach would consider themselves as channels, to be kept open with any means, through which a transcendental power (be it called "inspiration," "deity," "music," "subconscious," whatever the flavor of the month suggested) could manifest itself.

The opposite approach, however, stresses (always in my view) the control, and the equilibrium made possible by that perfect control.

If this is even partly true, it would seem to me that actually, for those who were and are often seen as to be indulging themselves and their egos, the self is in fact less central, a feature that should be kept in check and effaced as much as possible, to keep the channels of the "inspiration" unclogged and to allow the free flow of that transcendental force at work.

On the other hand, the perfect control pursued and prized by the opposite doctrine would require an incredible amount of work on the self, physical, intellectual, spiritual -- you name it -- bringing it effectively at the center of the artistic creation.

France

cellochris replies: I'm not taking any particular side as to which is better, "romanticism" or "classicism." I'm just stating what I've observed many times.

For the most part, I agree with what France said. But, I would add that many times the "romantics" are often expressing something that is completely narcissistic. And to even take it a step further, to me personally, the types of musicians in the non-classical genre like Yanni, John Tesh, and many, many others who "don't sweat the small stuff" but want to make you "feel" the music; and, those types who think that their playing is somehow "divine" or "inspired by God," are no less egocentric than those who are demonstrating the depths of their artistically and technically refined sensitivity to correct phrasing and style with the composer's intentions always at the helm.

In my more humble knowledge and opinion of the deeper matters in the classical realm, I love listening to Yo-Yo Ma and his gushy vibratos and swells as he plays the Rococo. I like to hear that, and I know that he's enjoying himself too, it's obvious. But, I have noticed that even when he is trying to play absolutely period and composer "correct" (as mentioned in previous paragraph) like as when he is playing J.S. Bach's "Goldberg Variations," somehow he still just sounds like he's showing off HIS stuff to the listener � kind of like Elvis... but that's just Yo-Yo's style. So, even though he's engaged mentally, and artistically (as far as I can tell), I don't think that he's ever claimed that his playing is "divinely inspired" and he seems very modest as person, but, if he ever did claim "sublime," he'd probably start dressing like Liberace and rolling on stage on a golden cart in his own mind!

On the other hand, when I listen to Janos Starker play the Elgar Concerto Op. 85, he seems to play in a manner that's just as romantic if not more so than Yo-Yo, but Starker does it in a way that makes it sound like he REALLY is feeling the "pain," the depth of emotion, and, conversely, the "elation" and heights thereof as if those were his own experiences, like he's a "slave" to the music. Starker seems to be thinking and doing more with each and every note and the gears seem to be turning in his head in terms of musicality more so as well. But, he seems to convey this precision as just a mere necessity to his greater "service" to the piece. So, I don't think of that as narcissism even though you basically have all the bases covered there; romance, feeling, appeal to a greater influence (composer), and even technical, musical, and stylistic aptitude.

And then, in another genre, you have Jazz soloists!! They are narcissistic in both ways! And yes, most of them claim a "divine" or "sublime" connection of some sort to their music with each and every sharp, flat, and 32nd-note pentatonic scale!

So, I guess it depends on the artist as an individual person, why they play, what drives and motivates them as individual human beings to play the cello in the first place as to whether they are a narcissistic romantic, a "classicism" romantic, a narcissist "classicist", or a romantic, "classicist", narcissistic! The question is: on a broader scale, how many of the performing cellists today and yesterday would still continue playing if there was no one around to listen to them play? Who knows, what do I know what's going on in their hearts and minds?

>> Orchestral Playing

So, I was listening to Beethoven's 9th on the car radio. I missed the beginning, so I didn't know who was playing until the end. There was a tremendous energy and a wonderful sense of ensemble in the performance. The orchestral was clearly a great, great group. But, while the phrasing was crystal clear in that everybody seemed to be breathing together, I didn't get the sense that each phrase had been analyzed to determine which notes were more important within each phrase, i.e. no "rainbows." I won't say who the orchestra was, but let's just say that it was one of the Top 5 in the USA. And this is something I notice frequently in orchestral performances, so this was not unique to this orchestra or this particular recording.

So my question is, do orchestras ever REALLY work on the music? Do they ever break down phrases into bits and pieces? Or, due to time contraints, is there an inherent limitation on the how much analysis goes into a performance, and therefore a limit on the level of musicianship?

Tim Janof

Gary Stucka replies: There's no question that there are time constraints. Do they affect "musicianship"? I don't think so, personally. If a conductor wishes to have the piece performed with as much attention to detail as Tim is suggesting, the conductor had better have the stick-clarity of a Maazel and bring his own parts. Additionally, these parts should be marked within an inch of their lives to achieve these details in the short amount of time that is conventionally allotted to rehearsal. It is simply not economically feasible or, for that matter, practical to rehearse a single piece with the same intensity and attention to detail as a professional quartet or other small ensemble. Imagine spending 100 hours or so on a Beethoven Symphony with an orchestra. At the very least, the orchestra would be bankrupt well before the first performance.

Are listeners missing anything as a result? Is there "less" in terms of the musicianship of a performance? I suppose it depends on the sensitivity and musical knowledge of the listener. Clearly, Tim's experience with the aforementioned performance was 'lacking' for him. From my own experience, we at the CSO have had a number of conductors that have spent so much time on details, that the performances have lacked any sort of cohesive structure. My opinion is that these same maestri would NOT have benefited from any additional rehearsal time--they're already missing the forest for the trees.

It's an interesting topic. Toscanini, Koussevitsky, Furtwangler and a few other greats from an earlier era had only marginally more rehearsal time than we do today. I can't imagine being more overwhelmed than I already am by the performances by these people. Celibidache, on the other hand, used to require many more hours of rehearsal than "normal" and I've always been bored to tears by his performances. Yes, one may hear more detail -- but then the performance becomes merely that -- a sequence of details. That, too, is really not acceptable.

Carter Brey replies: Just cruising by here and caught this thread. It happens to coincide with my biggest personal issue as an orchestral player.

My beef: old-style orchestra players who expect to be spoon fed everything. You know the type: they show up at the first rehearsal of the Bartok Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta without having looked at the notes and passively await instructions from the podium while they try to separate the double sharps from the double flats. My hope: more players in the Orpheus mold who take responsibility for the music. Of course there is limited opportunity for this in a large orchestra with some clown on the podium waving his arms and thinking about his next photo op. Of course this is easier for principal players than for section players. But to say that one is too busy to worry about anything but one's own part is inexcusable and depressing, at least when it comes to standard repertoire.

I find myself regularly having to remind players in my band to listen to woodwind or brass soloists and breathe with them, or not to rush walking bass lines. This is not rocket science, folks. Among many such unpleasant encounters, I remember with particular fondness asking the double basses to listen to a horn entrance in the slow movement of the Eroica Symphony (surely familiar enough that musicians in a major famous symphony orchestra can be expected to listen vertically, even with only two or three rehearsals?) so that they would stop coming in early. Naturally they blamed it on the conductor and bitterly resented my intrusiveness. Excuse me for asking for a minimal level of participatory musicianship and ensemble awareness. In fact I would codify this as an immutable Law of Orchestral Dynamics: the less accomplished and secure an orchestral musician, the more likely he or she is to erupt in a display of ruffled feathers and offended dignity and to point out how many long decades he or she has played in an orchestra. The opposite is absolutely true: a responsible, alert, intelligent and well-trained musician with a strong chamber music background will usually act quickly to sort out ensemble problems on his or her initiative, often with the help of a full score, which -- mirabile dictu! -- is after all not the exclusive possession of a conductor.

If the conductor wants to follow along and add a few comments to clarify a general concept, hey, that's icing on the cake. There are some -- a few -- who can make the difference between an accurate performance and a transcendent one.

This theory of responsibility works both ways. Last season I came in spectacularly wrong in the slow movement of the Beethoven Violin Concerto. My colleagues, after the concert, started to commiserate with me and tried to blame it on Kurt Masur's ambiguous beat. No, I will not have it. I was not prepared sufficiently well to know the solo part at that moment, and the fault was with me. It was a good lesson whose freshness I hope never wears off.

Ryan Selberg replies: Several days ago, at an intermission of a rehearsal, I sat and talked to a colleague in the viola section, who has been with the orchestra 26 years. He mentioned the possibility of his going back to school, to getting another degree. I casually asked if it would be in the music field or another, and he said definitely in something else, although he had no idea at present what that might be. And it would be with the intent of a career change. He then elaborated on his extreme frustration with the plight of a section player, using words such as "repressed," and "demoralized," as well as stating that it was virtually impossible to get emotionally involved with many of the major works in the repertoire. Tchaikovsky 4 was specifically mentioned. He also pointed out that in the 26 years he has spent in the orchestra, he has never had the conductor, nor any member of the management team, come to him to ask him personally how he was, what he thought about his job, or about the orchestra in general, etc. His wife is an employee of a major pharmaceutical company, which regularly provide for employee interaction with the management. This player is also a very capable player, who plays chamber music and does the Teton Festival in the summer.

I find this rather disturbing, but probably not unique. I suspect many of the better players in an orchestra's string sections (unlike the winds/brass, where the individual is much more involved in musical decisions, being usually the only one on a particular part) feel similar frustrations. His complaint of lack of advancement opportunities, however, is inherent in a union contracted orchestra, with titled players (no matter how good or inept they are) granted immunity from challenges from within the section. We do, however, have a rotating string section, including violins rotating back and forth between first and second.

As the current chair of the orchestra's Artistic Advisory Committee, we have been making some good strides in communication with our Music Director, as well as with our management. With our recent merger with the Utah Opera, we have a new CEO who has repeatedly made comments on wanting to create much more focus on the players. I have been mulling over in my own mind as to whether to contact her directly on this issue, or wait to present it as part of an agenda with my committee. I do think she will be receptive to hearing the comments (names will be withheld, for protection of the individual in question, unless he is willing to come forward to further address the issue). I don't know what specific steps can and will be taken, but this current thread certainly encourages me to proceed further with this issue.

Carter Brey replies: Ryan, a musician who defines for me the model of a caring and conscientious principal player, has hit on a very serious problem. Where else would one encounter such a hidebound corporate culture? I see incredibly talented people sitting in the back of my section who are stressed out and frustrated by their lack of input and the difficulties of their position on a daily basis. Yet my offer to sit in the back stands for a week to see firsthand how hard it was to play from that part of the Avery Fisher Hall stage (I was a section player in Cleveland, but Severance Hall is a much more forgiving environment) was met by derisive laughter from the Personnel Manager. Similarly, a backstage section rehearsal of La Mer while on tour recently elicited unkind snickers from non-cellist onlookers (we kicked butt in the concert, anyway). Anything out of the ordinary box seems to be viewed as a threat.

I'm thinking about possible anodynes to feelings of disenfranchisement. So far in our orchestra there are a major chamber music series (at Merkin Hall) open to participation by any interested players, and membership on various committees (Artistic, Orchestra, etc).

But what about fostering better communication by having regular section meetings? These things happen now and then informally, on the occasion of a birthday, for example. But what about a section lunch? A forum in which people could really air thoughts. I've had a couple of these under less than happy circumstances, but at least players could air their feelings about important issues. Perhaps some people would see this as risible and naive. But I believe that there is real value in sharing common goals, even those as simple as spending time together. Isolation breeds and magnifies the common problems to which Ryan refers. Some sort of community identity is, I think, one possible step toward dealing with those problems.

BA replies:I have a rather interesting perspective on this having spent the last 8 years as a principal and the last three months learning the ropes in a section in the New York Philharmonic. And perhaps I am still too new to appreciate the frustrations fully, and perhaps I am rather lucky in that I chose to be here. Of course, I had to fool them into choosing me first, but there weren't really any other section positions I would have passed up principal opportunities for. The situation here in New York was unique for me, mainly because of the respect I have for Carter and other players here, and also because I wanted to live in New York.

I have seen life on both sides. I've been the 'big fish' in the murky pond, done the solos (after playing the solo so many times, I can't listen to the second movement of Brahms 2nd piano concerto on the radio without gradually beginning to sweat and feeling my pulse race as the third movement draws near!), done the concertos, had the conductors attentions (ugh!). As principal I tried to involve myself with bettering the situation in every way I could think of, including serving on committees and providing a conduit for the concerns of the section to management. As far as a 'manager' of the section, I found that the best way to lead was to make people feel involved in a drive for a common goal. It didn't matter what god-awful musical crimes were going on around us, we were going to be a good section anyway. I tried to be open to exchange with the section -- people would constantly ask questions to clarify points, and at other times I talked a lot to them about the sound I was after. People suggested bowings (good changes were free, nudnik changes cost $0.50). I think a sense of integrity and community is infectious. I don't know how successful I was, but I tried to foster a sense that we were all in it together and that we as a section were going to get it right, regardless of what the rest of the orchestra did.

What is different sitting in the section? Not much, really. There is a need to focus on playing with the leader and the people around you, as well as those in other sections, and you must blend sound and strokes rather than dictate them, but it is all pretty much normal good musicianship. The things that are frustrating in the section are the same types of things that are frustrating as principal. Things that undermine the performance that are beyond our control to change. Be it basses coming in early and too loud, wind chords that never get tuned, a conductor's odd tempi, or a stand partner's odd polyrhythmic hacking in lieu of off-beats. When you are principal there is constant pressure on you to be prepared, while in the section you COULD, if you chose, probably hide somewhat and get away with not being prepared. It becomes a question of integrity.

But this is where the cardinal rule of life comes into play. You get out of it what you put into it. Whether as principal or in the section I have found that the better prepared I am, the more I understand the music and what is going on, and the better shape I am in, the more I enjoy playing and the more I get out of it. We have the chance to perform every week the greatest music ever written (OK- MOST weeks...). How can we not care about it, no matter what goes on on the podium or around us? It is not just that people stop contributing because they become bitter, it is that people become bitter because they stop contributing.

True, you may not always get a lot of ego gratification playing in a section, (though there are other places outside the orchestra to turn for that), but there is no reason because of that to miss the musical gratification that is possible by involving yourself in the process. I enjoyed being principal because I felt I was able to contribute to the musical process and to help bring my colleagues together as well. And I enjoy being in the section here for the exact same reasons. I know Carter, and I suspect Ryan as well, bring a similar philosophy and integrity to their work. The pre-concert, voluntary La Mer section rehearsal in Manila was a perfect example of what I'm talking about.

I came from a unique place. I started my 'serious' musical career fairly late, after another life in mathematics. I chose a life in music rather than having it forced upon me, and it helps me to appreciate what we have from another perspective. The most rewarding thing for me in my musical life has not been any achievement, or any performance or award. It has been the fact that I have learned things that make me a better musician and a better cellist than I was at age 25. Perhaps someday I will want to try for principal positions again, but I am happy and grateful to be where I am, learning things that will benefit me throughout my musical life.

Life is interesting only so long as we are learning and thinking, and the responsibility for that belongs with the individual. We are too quick to place the blame for frustrations outside ourselves. Believe me, I have no love for conductors (or semi-conductors or resistors), but the greatness of the music will always overrule the frustrations they may inflict.

>> Bach c minor Prelude

I've been working on the great sonorous prelude of the Fifth Bach Suite, which is probably a bit ambitious considering that I've only been playing for about 20 months. But it's one of those pieces that have always inspired me, and having got a large part of the first and second suites under my belt (well, to my ears anyway...), I thought it was time to give it a go.

In fact it's turning out to be much less difficult than I'd expected. But goodness, there are a couple of double stops that I'm finding rather tricky, even though I have long fingers and almost a lifetime of playing the classical guitar. Any help or advice would be much appreciated.

The first and perhaps worst one comes up right in the third bar, which opens with an E flat on the D string and a C on the G string. It's not one of those double stops that you can fudge -- it's absolutely got to be right or it sounds terrible. I find that it helps if I bring my whole hand round the neck as far as it will go, so that I'm attacking the double stop very much from above, but it's really quite painful to hold that position for more than a very short time.

What do others do with this one? Roll across the double stop so that you take the two notes one at a time? Transpose it to the G and C strings, where you can take it higher up the fingerboard? Or just grin and bear it?

Mike

Stephen Kates replies: I read your plight to conquer the "impossible dream" in measure 2 of the c minor Prelude of Bach Suite #5. A hand enlargement might do the trick (very expensive and not always painless, especially in the early months of engraftment). Another 20 months of scales in thirds, sixths, sevenths octaves, and even ninths can do wonders for your ability to stretch, but I am afraid you will become the 2003 poster child for tendonitis. Even if you develop a hand the size of big foot and can reach that in half position you will never "dare" to vibrate on the third of Eb/C 1-4. For fear of losing your pitch and falling off the fingerboard.

I have a solution that will not cost a dime and is 100% guaranteed to satisfy you.

On the fourth beat of measure 2 shift on your trusty second finger (without sliding to it) to fourth position to the E-flat on the g string. Play on the g string 2-4-1 AND THEN shift up one half tone to 1 on the E-flat. Now PLAY the C that used to be SOOOOOOO hard on the C-string AS A HARMONIC.

BINGO you now have the impossible third E-flat/C IN TUNE and, guess what, if you want to you could vibrate on BOTH notes then happily move to your open C string for the second beat and even more you could play a tenth E-flat/open-C at the same time just as Bach wrote it.

Good luck and remember the trick is not overpowering the cello, but mastering it by outsmarting it, and using what you have got both physically and intellectually.

>> Discussion about Steven Isserlis' recent performance with the New York Philharmonic

First the good points. Isserlis is a very intelligent and thoughtful musician with a good ear for tone color and a sense of timing. He produced certain turns of phrase that were truly very beautiful. He is clearly a sensitive and intelligent musician.

The problems however were, in my opinion, substantial. To begin with, let's talk about the gut strings. He is playing one of the greatest cellos in the world -- the Feuermann Strad. I grew up listening to recordings of that cello, and once in a while I still hear that voice come through. I don't think the problem is that one cannot play gut strings on that instrument. Feuermann did until the steel A's became available towards the end of his life. The problem is that you can't play on gut strings the way Isserlis does. He rips into them using a lot of pressure and not enough bow speed and produces a sound that can be quite metallic, as the New York Times noted. And when he plays fast -- and he played wildly fast in many runs -- it became a scratchy inaudible blur. The main impression he left on many musicians here was of a poor, scratchy sound. His choice to play fast passages on the lower strings didn't help this either. As I said, this is not an issue of playing on gut strings but of the way in which he plays on them, but I don't have much experience playing on gut so I am guessing as to the exact problem in his approach.

The second major problem was the vibrato. He has an obsession with playing certain notes non vibrato, or starting the vibrato only halfway through a note. It works for Ella Fitzgerald, but not for Tchaikovsky. To add to that, the vibrato often became overly hysterical. Only rarely did I here a nice even relaxed vibrato that simply let the instrument sing naturally, but when I did the sound was wonderful.

In terms of phrasing, as I said he did some beautiful and spontaneous things. For my taste it still ended up on the overdone and pulled-apart side of things in compared with the phrasing styles of the generation I prefer (Feuermann, Casals, etc.). My overall impression was many little pieces, some of them very beautiful, but not held together with logic in a way that produces truly great musical beauty. But IMHO most people I hear these days play that way, so maybe I was just born 40 years too late for my own good.

He did stumble on some nights on the predictable demons in that piece -- bow control and high harmonics, but his technique was certainly sufficient for a major soloist. He played the original, which I am beginning to really like. But he played the Fitzenhagen notes in a few places for reasons I don't understand. Perhaps he has different sources than I do. Also he played the trill variation with a vibrato trill that was kind of shocking, though I think it sounded fine. He had a couple of very courageous fingerings as well.

Overall he is a musician of intelligence and talent, but my general impression from this series of concerts was that issues of sound, vibrato and continuity of the large phrase lines made the performances much less than they could and should have been. The overall impression I got from my colleagues was I think similar (a typical comment being "You should have heard Carter play it." Carter also played the original in his New York Philharmonic debut). Carter is indeed a friend and collaborator of Steven's though, and may well have different and perhaps more insightful opinions since he is more familiar with Steven's playing. Anyway, that was my take on it, after watching the dress rehearsal and all four concerts.

BA

Carter Brey replies: This thread, of course, was interesting to me. I'll add a few comments to those of my colleague, BA. My friend Steven, who happens to be a first-class player, is deserving of more attention in a country that is obsessed with one cellist.

BA and I sat together for last night's performance of the Tchaikovsky, and I do agree with much of what he wrote here. Although I said nothing to BA as we listened last night, what was going through my head was a debate on the merits of being honest with Steven about the problem of his approach to gut and what seems to be a consistent vibrato problem in very high registers.

In addition, for many years Steven and I have had an amiable running gag argument about gut vs. steel, and the truth is that I consider gut strings to produce much more of what to me is a metallic sound than metal itself. To be more precise, gut A strings sound to me steely while the lower strings sound dull and unable to take advantage of the full range of warmth and color of a great instrument.

I wish BA had heard the chamber concert at the Y, because here I was able to enjoy Steven's playing up close in a far more intimate environment than Avery Fisher Hall, which from the soloist's chair looks and feels like the Grand Canyon. The sound he produced there was, in a word, ravishing, and the music making was subtle, intelligent and passionate.

I'm afraid I can't share my respected colleague's unalloyed enthusiasm for another generation; I have to take their work on a case-by-case basis. My suspicion glands start working overtime whenever I feel that someone is falling victim to the "They Don't Make 'em Like They Used To" syndrome. Pianists and singers especially seem prone to this disorder.

Many were the hours I spent as a student studying old recordings by folks like Casals, Feuermann, et alia. But I found what I perceived to be their limitations just as enlightening as their moments of surpassing greatness. Casals' Bach Suites? Yes! Monumental and deeply satisfying. His 1920's rendition of the Preislied from Meistersinger? Hello? Had he ever heard the opera? Get a clue! I adore his playing of miniatures from Goyescas. As a child I inherited some ten-inch shellacs of that stuff from my grandfather. But the Schumann Concerto? Sorry -- give me Slava with Rozhdestvensky and Leningrad for a real soul-searching Schumann experience. I find the Prades Festival recording painful, pompous, and embarrassing, which is just how I would characterize Slava's Bach, in fact. All of which is to illustrate my feeling that we're fortunate to have an ongoing colloquy about music that spans generations. Outstanding talents like Truls Mørk, Boris Pergamenchikov and Steven Isserlis are not, ipso facto, inferior to their predecessors in my opinion.

I find that one of the unsung heroes of that older generation was the great pedagogue Felix Salmond. I heard an antiquated recording of him playing the Grieg Sonata that captivated me for its classical poise and beauty of sound. I wish I could have heard more of him.

An admission: when I have time to listen to music, I usually listen to pianists rather than cellists. Glenn Gould, Murray Perahia, Svjatoslav Richter (whom I was lucky enough to hear twice in recital), Leon Fleisher and Artur Schnabel have always been my musical lodestones. I'm determined to be reborn as a pianist so that I can spend my next life with the Mozart concerti.

BA replies: In reading what I wrote the next day, I find what I wrote was more negative than I had intended. I did mean everything I said, but somehow the overall impression comes out sounding as if there was little of merit in the performance. Isserlis has a really wonderful talent and does interesting and often beautiful things and I was glad to have the chance to hear him play. Had I not felt that way, I wouldn't have kept going back to hear more. He makes me think, and he makes music. I do wish I could have heard the chamber music at the Y. I have a feeling that would have been Steven in his element.

As far as 'old school' vs 'new school' Carter makes a very good point. It is too easy and intellectually lazy to paint with a broad brush. I have grown up very much focused on my love for the 'old world' primarily because of my love for a few particular players, but even these fantastic players have limitations in certain repertoire -- Heifetz in Bach is not Heifetz in Vieuxtamps. And my dis-inclination towards the present stems more from negative impressions of a few players than from a comprehensive knowledge of modern players. There is still great and thoughtful music making going on out there, though I often think it doesn't get the attention it deserves, and our goal must always be to go beyond what has been done in the past.

>> Raya Garbousova

Has anyone heard of Raya Garbousova? She was a student of Casals, and my teacher has but one of her recordings (Stravinsky, Suite Italienne), and it is fantastic! I was just looking for some info on her if anyone had it.

Brian

Stephen Kates replies: She was one of the world's greatest cellists, artists, teachers, and since her death a few years ago the cello world can only imagine its loss. My knowledge of her began at an early age as I had the opportunity to be a camper at a music camp with her two sons Paul and Greg Biss. Though I was far too young to have an inkling of "who" she was at that time it gave me the chance to meet her a number of years later when I was a teenager.

I called her up to invite myself to her hotel (The Ruxton) and played the Arpeggione for her first to last note (by memory). What a nerve I had. She looked at me and said, "Don't play from memory even if you know it faultlessly." You deny yourself the chance to 'see' something you might have missed that Schubert wanted, not what YOU wanted." Awfully good advice to a sixteen-year-old. Thus began a friendship that blossomed into an enduring collegial closeness that I am proud to say lasted until the day she died.

I would often visit her at her home in De Kalb when I was anywhere near, it actually became a "must." We wrote to each other and she would show up unexpectedly at my concerts and, boy, I would get butterflies seeing her (all 5 feet tall) charge into the dressing room to greet me after a performance. She was one of those people who knew more about you and your playing than you did yourself. Very scary. But her warmth and genuine affection disarmed me from the moment she entered the room and said, "Stephen ........" with the thickest Russian accent imaginable.

We shared honors one year at the Piatigorsky Seminar with Bernard Greenhouse and I was the " kid" on board. I enjoyed her teaching immensely and in the evening she told stories about Casals, Barber, Martinu, Koussevitsky, Piatigorsky, Heifetz, Feuermann, Alexanian, Prokofiev, to name a few. She knew them all and they all loved her, it was unavoidable.

All I can say is that I am a much richer human being and a much better cellist for having known her. I can not imagine having not known her. She was one of the reasons I became a cellist and I treasure each and every memory of those years we had together. Now run and get her recordings and read about her and talk to people who knew her and try to get some idea of how great a human being and musician she was. It is your responsibility and I would think, a privilege.

Eric Edberg replies: I first met Raya Garbousova when I was studying with Bernard Greenhouse at SUNY Stony Brook. They were dear, old friends, and she visited twice, I think, during the year I was doing my master's degree there. She would fly in from Illinois bringing her bow with her, and then demonstrate using Mr. Greenhouse's great Strad when she gave a masterclass. In one of those classes, I played the Rococo Variations for her, and she had many wonderful suggestions. She also had a wonderful anecdote about that piece which we all got quite a kick out of.

As a young woman, she told us, she did a grueling recital tour with her sister, a pianist. One of their big pieces was the Rococo, which by the time of the tour she had performed innumerable times. It's all too easy to become exhausted on a big tour, sleeping in strange hotels, traveling at all hours. One night she was particularly tired as she began the Tchaikovsky. Things went fine for the first variation or two, but the next thing she knew it was the final variation, and she had no memory of the intervening ones. After the concert, she asked her sister, "did everything go well in the Rococo?" Her sister replied, "Of course! Raya, you know that piece so well you could play it in your sleep." To which she replied, "I think I just did!"

1. Feuermann Competition Prizes

The following are the prize winners for the "Grand Prix Emanuel Feuermann" in November:

Fanfare Magazine recently published an interview of James Kreger. Check it out!

http://www.geocities.com/jameskreger/articles/fanfare.htm

3. New Principal Cellist of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra

The following is excerpted from the Detroit Symphony Orchestra press release:

"Following four international auditions since 1999, the Detroit Symphony Orchestra has found its new Principal Cellist. Robert deMaine, age 32, of West Hartford, Connecticut, has been named to this post. "deMaine's previous distinctions have included First Prizes from the Saint Louis Symphony/Union Electric Young Artists Competition, the Chicago Cello Society Competition, the Naftzger Young Artists Competition, the American String Teachers Association New York Solo Competition, the Julius Bloch Awards, the Corpus Christi Young Artists Competition (Cello category), the Piatigorsky Seminar in Los Angeles, a Career Grant from the Helen M. Saunders Charitable Trust, and most recently, and the Premio Sipario di Milano for Excellence in Classical Solo Performance (he is the first cellist to be selected for this Italian arts and entertainment honor.)

"A fellowship alumnus and magna� cum laude graduate of the Eastman School of Music and Yale University, his teachers have included Steven Doane, Paul Katz, Aldo Parisot, Bernard Greenhouse, Janos Starker and Luis Garcia-Renart. An avid chamber musician and solo recitalist, he has performed frequently as guest artist and participant in the music festivals of Aspen, Norfolk, Chautauqua, El Paso Pro-Musica, Utah, and Marlboro (also performing with Marlboro Music in New York and Washington, D.C.); Mexico's San Miguel de Allende Festival, Argentina�s Pan-American Cultural Foundation in Buenos Aires, and the Heidelberg Castle Festival in Germany.

"As a teacher, deMaine has presented master classes throughout North and South America, Europe and New Zealand, and has served on the faculties of the Hartford Conservatory, the American Festival for the Arts in Houston, and was Assistant to Steven Doane and Paul Katz at Eastman. Also a composer, deMaine has written various music for the cello, which he regularly performs, including his 12 Etudes-Caprices, Op. 31 (1999).

"Born into a musical family of French and Polish extraction, deMaine began musical studies at the age of four with his mother and sister, both accomplished cellists. He made his recital debut at age ten, followed by his concerto debut at age 12 with the Oklahoma City Symphony Orchestra. Shortly thereafter, he came to the attention of legendary cellists Leonard Rose, and Pierre Fournier, who predicted a great future for the young musician, the former calling him "a profound talent" and accepting him as one of his last students.

"deMaine plays alternately on three cellos, but his primary instrument was made in America in 1992 by Jon Van Kouwenhoven. He has an instrument that has been in his family for several generations, a Venetian cello reminiscent of a Matteo Gofriller, as well as another American-made cello, a 1994 by David Caron."

4. ASTA with NSOA Conference

Celebrating Strings: All Together Now

March 27-29, 2003

Ohio State University

Columbus, OH

Cellists will find many opportunities to network with other cellists, explore cello literature, try cellos and bows, and attend fascinating sessions at the first-ever ASTA with NSOA National Conference March 27-29, 2003 on the campus of Ohio State University. The gathering will recognize the wealth of our rich traditions as well as offer members new horizons in teaching and performing. Some highlights include: a Cello Master Class with Paul Katz; a Cello Technique Class, and several workshops related to cello playing. Hear the National High School Honors Orchestra under Jose Serebrier, see Mstislav Rostropovich as he accepts the ASTA Isaac Stern International Award. Hear university and youth orchestras. Observe the First Alternative Styles celebration and awards. Over 60 Sessions including:

For more information please visit http://www.astaweb.com/conference/index2.htm or call 703-279-2113 ext. 14.

There will be clinics and performances that address the needs of private studio teachers, elementary and secondary string and orchestra teachers, university string teachers in both applied and music education areas, string students, Suzuki teachers, professional classical and non-classical performers, non-string performers who teach strings in schools, and administrators. For string players this will be the "place to be" in 2003.

5. International Summer Music Academy Leipzig

The International Summer Music Academy Leipzig will take place July 16th through August 5th 2003, in Leipzig, Germany. There will be intensive individual and chamber music instruction, master classes, workshops, lectures, and excursions. The cello studio will be lead by Rimantas Armonas (Lithuanian National Academy). Chamber music will be taught by Toby Appel (Juilliard) and Roland Baldini (Leipzig). There will also be Bach studies and reviewed student concerts in major halls (Gewandhaus). Instruction will be in English.

For more information go to: http://www.hmt-leipzig.de (click on Summer Academy in English version) or write to: academy@hmt-leipzig.de

6. Revised cello book

A new revised and expanded editon of Victor Sazer's New Directions in Cello Playing is expected to be ready ship in January, 2003. "New Directions in Cello Playing introduces natural, tension-free ways of playing and anatomically improved techniques that prevent performance-related injury. Its innovative approach to body use increases efficiency and improves performance. This revised and expanded edition also includes new strategies for teaching beginners."

7. Award Winners

8. More Cello News

A cello news link has been engineered using Google.com's features. Be sure to bookmark it.

http://news.google.com/news?hl=en&q=cellist+cello&btnG=Google+Search

American Cello Congress

The next American Cello Congress is scheduled for May 17-22, 2003, at Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona.

Adam International Cello Festival and Competition

The festival was set up in 1995 by Professor Alexander Ivashkin and is run by the International Cello Festival Trust, a charitable trust here in Christchurch. The Festival is biennially held in Christchurch New Zealand. It attracts the world's best young cellists to compete in a competition, judged by world renown cellists who also appear as guest recitalists. The next festival is July 2003. http://www.adaminternationalcellofest.com.

Kronberg Festival

The 6th Cello Festival in Kronberg, Germany will be a memorial to Pablo Casals, starting on the 30th anniversary of his death. The dates are October 22-26, 2003. http://www.kronbergacademy.de .

Manchester International Cello Festival

The Royal Northern Conservatory of Music Internation Cello Festival in Manchester, England, has been set for May 5 to May 9, 2004.

Cello Festival Dordrecht

Cello Festival Dordrecht (Netherlands) May 24-27, 2003. http://www.cellofestival.dordt.nl.

World Cello Congress IV

Plan ahead! World Cello Congress IV will take place May/June 2006 at Towson University, Baltimore, Maryland. Cello Congress V is also listed on their website - May/June 2010! (There are also rumors that World Cello Congress IV will take place in 2003 in Israel. If anyone knows, could they contact me?) Also promised is a "Gala Benefit Performance" in 2003 to raise funds for WCC4. "Many of the greatest stars of the music world will join forces to present a one-of-a-kind event not to be missed." Concerts, recitals, masterclasses, workshops, symposia, exhibits, receptions. http://www.towson.edu/worldmusiccongresses.

For those who attended World Cello Congress III, videos are now available at $30 (includes shipping): http://www.towson.edu/worldmusiccongresses/video.html.

** If you know of any other cello events happening around the world,

please send word to Roberta Rominger, roberta@rominger.surfaid.org

**

(Please do not abuse this valuable service; check local libraries and resources before contacting Sarah.)

If you know of newsletters, teaching materials,

references, lists or articles that should be added to ICS Library, please

send data to michelj@cwu.edu. (Library

contents will be available to all Internet users; please include author

and written statement of release for unlimited or limited reproduction.)**

2. The American Youth Cello Choir

3. Rolland Bows

4. Alexandre Snitkovski

5. Creative Imperatives

http://www.creativeimperatives.com

6. Tulipan Quartett

http://www.tulipanquartett.com/

7. Help the ICS

http://www.cafeshops.com/cello

8. James Kreger Articles

http://www.geocities.com/jameskreger/articles/index.htm

| Direct correspondence to the appropriate ICS

Staff Editor: Tim Janof Director: John Michel Webmaster: Eric Hoffman Copyright © 1995- Internet Cello Society |

|---|